Platform Features

By Need

By Industry

Partner Program

Our Partners

Resource Center

{ "term_id": 164, "name": "David Thomason", "slug": "david-thomason", "term_group": 0, "term_taxonomy_id": 164, "taxonomy": "wpx-authors", "description": "", "parent": 0, "count": 12, "filter": "raw" }

WARNING: If the title isn’t clear enough, this might spoil your fun playing Wordle.

Like many competitive families around the world, my family became avid Wordle players shortly after it was released.

Then one day out of nowhere, Grandma announced an ironclad approach for consistent success. She explained that by using two devices, you could solve the puzzle on one, and use the other device to submit the winning solution with fewer tries. This would almost guarantee a victory over the rest of the family.

After I recovered from hearing such a revelation, I got curious about what other schemes could be exploited to increase the chances of winning. Since I work for an API security company, I wondered if I could hack Wordle through APIs.

Using Google Chrome and the built-in developer tools, I quickly realized the application reveals the daily solution to the puzzle before the first guess is made. All with the help of a JSON formatted API.

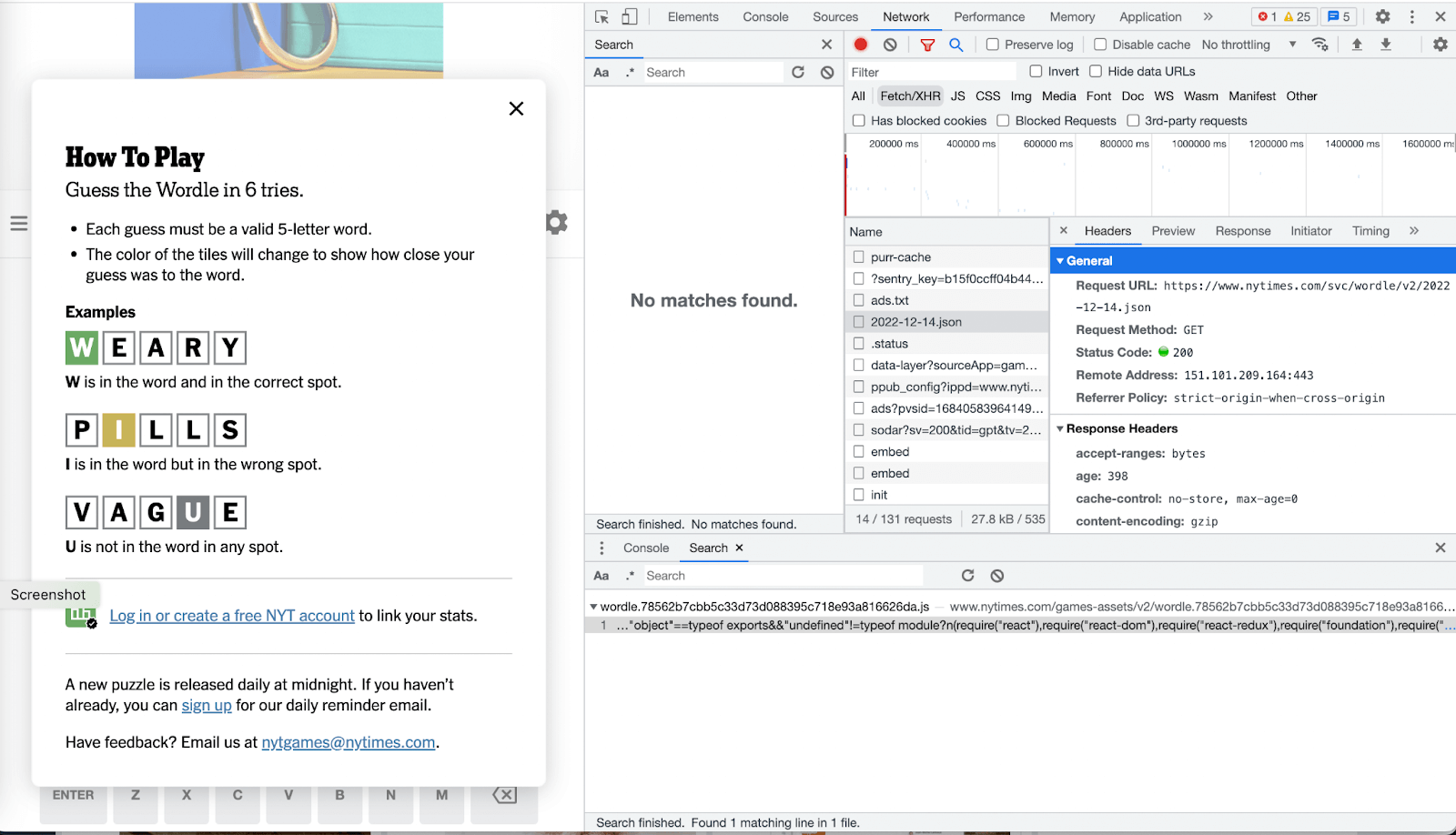

To do this yourself, open the developer view on your browser, and navigate to https://www.nytimes.com/games/wordle/index.html. Click on the “Network” tab, and select the “Fetch/XHR” filter option (make sure you refresh the page).

In the “Requests” cell, click on the JSON API with today’s date. What you’ll see is an API GET request to the Wordle service: https://www.nytimes.com/svc/wordle/v2/2022-12-14.json.

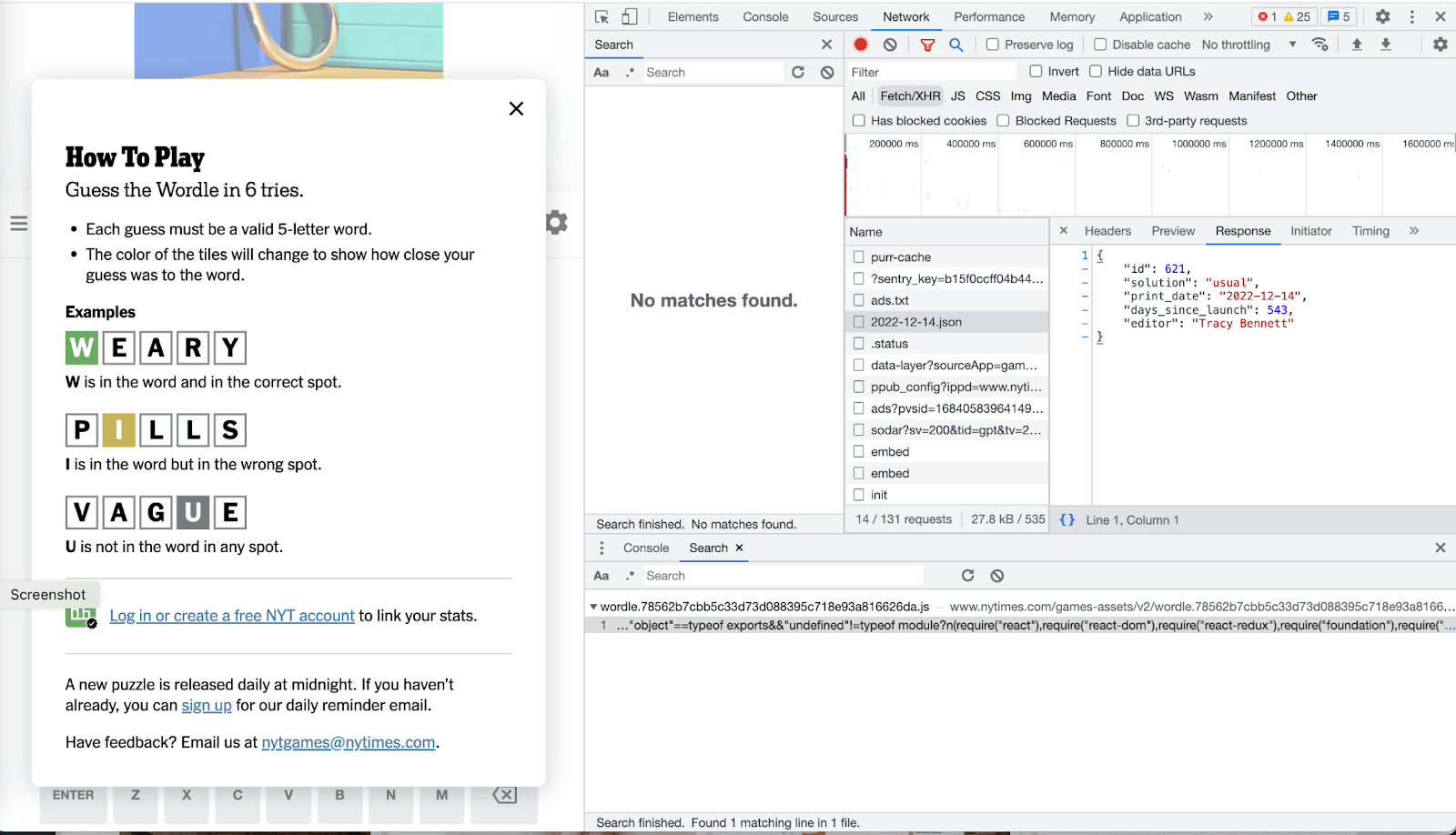

Next, check out the “Response” tab, and you’ll see the information provided by the Wordle service – including the answer to the day’s puzzle. You might want to press the “{}” button to see easier.

How fun is that? Now I can just view the API data types, see the JSON data for today’s puzzle, see the solution, and outsmart Grandma!

But what about tomorrow’s word? Well, that took just a little bit more effort.

Using the command line interface in my terminal app, I chose the command “curl” for my tool. “Wget” probably would work too, but I’m more comfortable with “curl”. By copying a few elements from the Chrome headers tab, I figured I could request the information for any given day. Sure enough, my hunch was right:

curl -X GET “https://www.nytimes.com/svc/wordle/v2/<date>.json”

This request revealed all the answers past, present, and future. Just replace <date> with any date of this format <YYYY-MM-DD> and voila.

For example:

curl -X GET “https://www.nytimes.com/svc/wordle/v2/2022-10-21.json”

produces the following output:

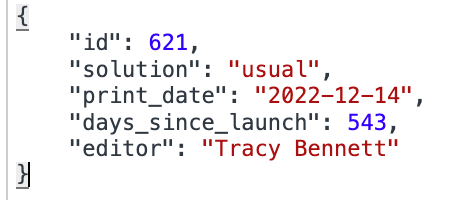

{“id”:621,”solution”:”usuale”,”print_date”:”2022-12-14″,”days_since_launch”:543,”editor”:”Tracy Bennett”}%

Going back to our Chrome output, we can easily confirm our data matches the output of the Chrome developer tools.

Now, unless Wordle words are somehow masking national intelligence data, it is unlikely that this hack will raise any red flags. After others exposed the entire list by reverse engineering the javascript code, it was published here. But what is interesting is the lessons of API security we can learn from this relatively simple hack.

Many developers are not trained on the OWASP API Security Top 10 and regularly make these mistakes when writing and publishing APIs. In the case of Wordle, one could argue that two of the top ten vulnerabilities were exposed:

API3:2019 Excessive Data Exposure: In this case, the application exposes the solution in the packets sent to the client. It is clearly excessive data. If the business logic were reversed, the answer could be retained on the server, and only the relevant responses returned to the client. Thus keeping the solution a secret. (In all fairness to the New York Times, this probably means more traffic/cost for the server and a potentially slower user experience.) But imagine this same vulnerability exposing sensitive information.

API5:2019 Broken Function Level Authorization: While API3 exposes today’s solution, by exploiting this vulnerability, API5 exposes all future solutions. A legitimate API call to the endpoint requesting a day other than the current day should result in an error. Thus, function-level authorization is broken, and a user can see the answer to tomorrow’s puzzle. Imagine seeing security keys or passwords because a policy, permission, or authorization code didn’t block the function from calling them.

I also realized that it may actually be possible to change future answers to the puzzle. Not to cheat, but to create a problem by changing the word to something offensive, or inflammatory.

My experience tells me it might be possible to use a POST method to change an item served by an API. Why do I think this? When the GET method is easily accessible, function-level authorization is broken, and authentication is not present (it isn’t with Wordle), it’s not a stretch to guess this is possible.

It actually would be relatively easy to test this. You simply do a similar “curl” command, only you use POST instead of GET and you have to include the “primary keys” for the record that is going to get changed. It might take a few guesses, but I suspect if they are vulnerable, we could figure it out in a matter of hours if not minutes. There are only a few fields in the request/response, so the number of options is relatively small.

Why didn’t I test this? Well, I didn’t want to break any laws, and thought it would be best left to the New York Times to address. I DID submit a responsible disclosure notice on the NYTs home page, and we reached out the NYT in multiple ways to make them aware.

In terms of resolving the Wordle hack, the New York Times would likely have a number of tactics at their disposal. But, it might be impossible to tell them which way is best until more is understood about the back end. That is one of the beauties of APIs. They don’t expose the backend.

To determine the right answer, there are a few things to ask.. The first question is, “Do you use an API gateway?” It is clear from the developer tools that they are using “envoy” and NGINX, but are they enforcing any policy on this endpoint? If not, they should block any kind of “write” permission to this endpoint (i.e., PUSH, PUT, DELETE).

If no API gateway or policy enforcement device is in line, then I would dig more into the architecture and ask, “How are you storing the daily words? In a database? In a flat text file? Are they hardcoded?” I would also like to know if it is simply a file. If so, then the fix may require some re-architecting of the applications.

Getting answers to these questions would lead to a pretty solid solution on how to protect the data. In any case, The New York Times might need to change the logic (or permissions) of the backend so that any kind of “write” attempts would not be permitted. In the worst case scenario, they will need to change the application such that the answer doesn’t leave the server until the user answers correctly. Or until a user misses on the sixth attempt.

As many organizations in the Fortune 500 would attest, the Noname API Security Platform would have been well equipped to uncover this issue well before it was discovered. Our platform secures APIs from code to production, and is purpose-built to identify vulnerabilities throughout the development lifecycle regardless of the severity.

For example, we once discovered that just by using the POST method, we could change the IP address of a streaming server for a major media company. You can use your imagination to determine what damage could be done through that vulnerability.

With that said, we’d love an opportunity to determine the origin of this predicament. Our comprehensive API security platform can automatically secure your environment, detect vulnerabilities before they’re exploited, and greatly reduce your API attack surface. We also integrate with your existing API gateways, load balancers, WAFs, and more, for complete visibility into your API ecosystem.

New York Times, if you permit me, I’ll test the potential to change words in the Wordle list. If the test is successful, I’ll make the last word, scheduled for October 14, 2027, “PWNED”. What do you say?